When We Choose the Commandments Over the Beatitudes

How American Christians learned to chase symbols of power instead of the posture Jesus actually blesses.

If you grew up in certain corners of American evangelicalism, you probably heard some version of this:

“This country started going downhill when they took prayer out of schools.”

“We need to get the Ten Commandments back in the classroom.”

I heard that constantly in high school.

Ironically, I was praying in school all the time. Before tests. Before lunch. Before games. In quiet moments when I was stressed or afraid. Nobody ever stopped me. Nobody could have.

At the same time, I remember hearing calls for public displays of the Ten Commandments in schools, courthouses, and other government buildings. When I was younger, I was in that camp too. I thought if we could just get those words back on the wall, it would somehow steady the country.

Fast forward to now, and those battles haven’t gone away. They’ve intensified.

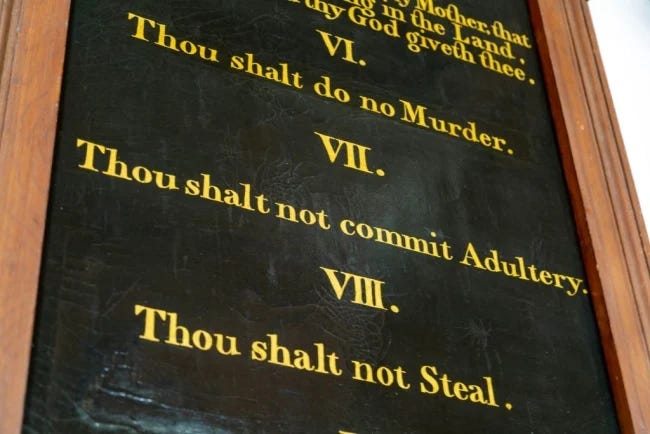

In Oklahoma, for example, Rep. Jim Olsen filed House Bill 1006 to require every public school classroom to hang a durable Ten Commandments poster—at least 16 inches by 20 inches, with the text large enough to read from anywhere in the room—beginning with the 2025–26 school year. Oklahoma Legislature Olsen said, “The Ten Commandments is one of the foundations of our nation. Publicly and proudly displaying them in public school classrooms will serve as a reminder of the ethics of our state and country as students and teachers go about their day.” OKW News

Around the same time, Oklahoma’s state superintendent Ryan Walters announced that “every teacher, every classroom in the state will have a Bible in the classroom and will be teaching from the Bible in the classroom,” and his office issued guidance telling schools to incorporate the Bible, which “includes the Ten Commandments,” as instructional support across multiple grades. KOSU+1

Louisiana has gone further, passing a law that requires a poster-sized display of the Ten Commandments in every public classroom, from kindergarten through state-funded universities, though the law is now being challenged in court. The Guardian+1

The Ten Commandments have become one of the favorite symbols in our public fights.

But here’s what I rarely, if ever, hear in those same debates:

“We need the Beatitudes back in our public life.”

“Our kids won’t make it without the Sermon on the Mount.”

The Beatitudes—Jesus’ opening blessing statements in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:1–12), where He describes who truly flourishes in His kingdom—almost never come up.

Why the Ten Commandments, over and over, and almost never the Beatitudes?

I don’t think that question is just about which Bible passages we like. I think it exposes something about what many American Christians are really afraid of—and what we’re really chasing.

Ten Commandments on the wall, Beatitudes in the background

When Christians argue about “taking America back for God,” the Ten Commandments always seem to show up.

They’re compact. They sound firm. You can engrave them in stone or print them on a poster. They signal moral clarity and authority. They fit neatly into campaigns about law, order, and “getting back to our roots.”

The Beatitudes don’t cooperate like that.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit…”

“Blessed are those who mourn…”

“Blessed are the meek…”

“Blessed are the merciful…”

“Blessed are the peacemakers…” (Matthew 5:1–12)

Those lines don’t slot neatly into political mailers. “Blessed are the peacemakers” doesn’t work well in a media environment built on outrage. “Blessed are the meek” is a terrible slogan if your main goal is to dominate.

So why the Ten Commandments more than the Beatitudes? Because commandments look like law. They’re short, clear, and easy to display. They feel at home in courtrooms and classrooms. The Beatitudes, on the other hand, describe a kind of posture—a way of being in the world that can’t be measured by test scores or etched into marble. The commandments can be mounted on a wall. The Beatitudes have to be embodied in a people.

And it’s worth saying out loud: the basic moral prohibitions in the Ten Commandments—don’t murder, don’t steal, don’t bear false witness—are not uniquely Christian. They’re shared, in some form, by Judaism, by Islam, and by most secular moral codes. Yet in our public fights we often present them as uniquely “Christian values,” while giving far less energy to the distinctly Christian, distinctly Jesus-shaped vision of the Beatitudes.

That’s part of the irony here: many American Christians who want to “take back the country for Christ” spend far more public energy advocating a generally shared moral code than they do advocating the particular, costly words of Jesus.

To be clear: the Ten Commandments matter. They reveal God’s character. They mark off real moral boundaries in a world that needs them. But the way we deploy them in American public life—especially in these display fights—often has more to do with symbolic dominance—in other words, keeping our faith visibly on top—than with humble discipleship.

The Jesus who perfectly fulfilled the Law is the same Jesus who then turned to a crowd and described His people in terms that sound nothing like cultural conquest: poverty of spirit, grief, gentleness, mercy, peacemaking, and joy in suffering.

So again: why do we insist on carving the commandments into stone in our public spaces, while Jesus’ own description of His kingdom people mostly gathers dust in the background?

We can win every symbolic battle and still lose our soul.

The prayer-in-schools myth (and what it reveals)

For years, I heard some version of this explanation for America’s decline:

“Everything fell apart when they took prayer out of schools.”

That sounds compelling until you slow down and ask what we actually mean.

Historically, the major court cases were about state-written or state-led prayers—teachers or administrators leading students in a specifically Christian prayer as part of the school day. Those rulings did not make it illegal for students to pray. They limited the government’s power to compose and impose prayer.

To be fair, not everyone today who says “bring prayer back to schools” is asking for a state-written Christian prayer. Some are concerned about student-led prayer over the loudspeaker, or public acknowledgment of faith, or moments of silence. The landscape is more nuanced than one slogan.

But much of the rhetoric I grew up hearing treated it as a tragedy that the school itself no longer led everyone in a uniform, usually Christian, prayer.

Here’s what I experienced instead:

I prayed in school whenever I wanted.

My classmates could too.

Nobody stopped us.

What changed was not whether Christians could pray, but whether the state would author the prayer, endorse it, and put its weight behind one faith expression.

Once you tug on that thread, real questions follow:

Whose wording gets used?

Which Christian tradition writes it?

What about Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, or nonreligious students?

Are we sure we want the government defining “acceptable” Christian prayer?

We also need to be honest about what’s at stake when we talk about “religious freedom.” True religious freedom is good news—for Christians and for everyone else. But freedom to practice faith is not the same thing as state endorsement of one faith. When we confuse endorsement with freedom, we start fighting for state-sponsored religion and telling ourselves we’re just defending our rights.

When we say, “We need prayer back in schools,” sometimes what we actually want—often without naming it—is official validation: our faith elevated, centered, and backed by the state.

That instinct is closely related to the Ten Commandments push. In both cases, the temptation is to equate public endorsement with faithfulness—and to treat the loss of that endorsement as a spiritual emergency.

So the next time you hear someone say “we need prayer back in schools,” maybe start by asking what we’re really afraid of—and how the Beatitudes might lead us to respond differently.

“But what about Joseph and Daniel?”

At this point, someone will rightly ask:

“What about believers in Scripture who did hold significant power—Joseph in Egypt, Daniel in Babylon, Esther in Persia? Doesn’t that show that God can work through His people in high places?”

Yes, it does.

Scripture absolutely includes stories of faithful people in positions of political influence. Joseph interpreted Pharaoh’s dreams and led famine planning. Daniel served pagan kings. Esther used her position to save her people.

And in Jeremiah 29, God tells exiled Israel to “seek the welfare of the city” where they live (Jeremiah 29:7). God’s people are meant to pursue the good of the places they inhabit, not ignore public life. Seeking the welfare of the city is about the common good, which in biblical terms includes attention to the poor, the vulnerable, and what Jesus later calls “the least of these” (Matthew 25:40).

That’s part of why there’s another irony that’s hard to ignore: many of the loudest voices demanding public Ten Commandments displays also argue that government should stay out of helping the poor and oppressed—that social safety nets, healthcare, and protections for the vulnerable are “not the government’s job.” In my experience, the overlap is striking.

If “seek the welfare of the city” means anything in a modern democracy, it has to include how we structure our life together for the sake of those at the bottom, not just how many religious symbols we can hang on the wall.

But notice what these stories and commands are actually about: faithfulness in exile, not building a religious majority that controls the state. These believers live under someone else’s rule. They don’t remake the empire into a “covenant nation.” They trust God and do good in the context they’ve been given.

That matters, because in the New Testament the dominant picture for followers of Jesus is not “moral majority” but scattered minority:

Peter calls Christians “exiles” and “sojourners” (1 Peter 2:11).

Jesus warns His followers to expect misunderstanding and mistreatment (e.g., John 15:18–20).

Paul’s letters are written to small communities embedded in an empire, not to a cultural bloc trying to keep its hands on the steering wheel.

Seeking the welfare of the city in a democracy can absolutely include voting, advocacy, and even Christians serving in office. My concern isn’t with influence as service; it’s with a posture that treats cultural dominance as essential to faithfulness.

A more accurate statement is something like: the New Testament spends far more time preparing Christians to live faithfully on the margins than it does telling them to secure cultural power.

A pluralistic country and a fearful church

Part of what’s driving all of this, I think, is the reality that America has become more pluralistic.

There are more visible religious traditions, more people who check “none” on surveys, fewer assumptions that Christianity is the default setting of American life.

In other words, white evangelicals in particular have less automatic cultural influence than they once did. Less home-field advantage.

If you listen carefully, you can hear the fear:

“We’re losing the country.”

“We’re becoming a minority in our own nation.”

“They’re taking everything away from us.”

I understand that anxiety. When I was younger, I absorbed a lot of the “Christian America” narrative. I believed that public Christian symbols—like Ten Commandments displays and school-led prayer—were essential markers that we were still “God’s country.” Losing those markers felt like losing God’s favor.

Over time, I began to notice something uncomfortable: when Christians are terrified of losing cultural primacy, we will do almost anything to hang onto it. I’ve felt that tug in myself.

One of the easier ways is to pour energy into symbolic fights—the sign, the poster, the monument—rather than into the slow, hidden work of forming people into Christlikeness.

It’s not that laws and symbols don’t matter at all. It’s that we often treat them as the main battlefield, and panic when we lose them, instead of asking whether this moment might actually push us back toward the kind of life the New Testament has been describing all along.

Jesus and power: what He did not ask for

When you read the Gospels with this question in mind—“What did Jesus ask His followers to chase?”—some patterns jump out.

In the wilderness, when Satan offers Jesus “all the kingdoms of the world” in exchange for worship, Jesus doesn’t say, “That might be useful for advancing My Father’s purposes.” He refuses the offer outright (Matthew 4:8–10).

Jesus describes His followers as salt, light, a little flock, a people on a narrow way—not as the default cultural managers (e.g., Matthew 5:13–16; Luke 12:32).

He tells His disciples that greatness in His kingdom looks like servanthood, not ruling over others the way “the rulers of the Gentiles” do.

Jesus puts it this way:

“You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them… Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant.” (Matthew 20:25–26)

The Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5–7) is not a strategy for holding onto power. It’s a description of what it looks like to live as citizens of God’s kingdom in the middle of a world where you often don’t hold power.

So when American Christians respond to pluralism mainly by trying to recover “our” symbols and visibility—whether signs, flags, or mandated classroom posters—we have to ask: Is that really the center of what Jesus formed us for?

“Law for the public, Beatitudes for the heart”?

A common pushback goes something like this:

“The Ten Commandments summarize basic moral law. Of course they matter in public life. The Beatitudes are about personal spirituality.”

I agree that the commandments mark out enduring moral boundaries that matter far beyond the church. Murder, theft, perjury—these are public issues. There is nothing wrong with wanting laws and norms that reflect those boundaries.

But I don’t think the Beatitudes are just about private feelings or “quiet time with God.”

Jesus is describing the kind of people who belong to His kingdom—people whose public presence looks like mercy, peacemaking, meekness, and costly faithfulness under pressure.

That absolutely has public implications.

A merciful people will care how justice systems treat the vulnerable.

Peacemakers will show up differently in political conflict.

The meek will resist tactics that depend on humiliation, cruelty, or constant outrage.

So yes, the Ten Commandments speak to public morality. But if we insist that the Beatitudes only apply in our private hearts, we’ve domesticated them. They were never meant to stay inside our prayer closets.

The deeper question is not, “Should Christians care about moral law in public?” Of course we should. The real question is: why do we so often fight to enshrine the commandments on the wall while ignoring the Beatitudes as our marching orders?

Not either/or—but what comes first?

I’m not arguing that Christians must choose between caring about laws and caring about character.

We can care about both public justice and personal integrity. We can care about moral boundaries and a Beatitudes-shaped church.

There are Christians and churches trying to do both. But if you look at where we pour our energy and money—the campaigns, the lawsuits, the fundraising emails—it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we’ve often flipped the priority.

We pour disproportionate energy into symbolic public battles—Ten Commandments posters, official prayers, religious monuments—while neglecting the slow, local, relational work of becoming merciful, pure-hearted, and peaceable people.

When signs and posters become a sort of shortcut—“If we can get the right words on the wall, the work is done”—they stop being a witness and start being a substitute.

The New Testament never promises Christians a world where everything is labeled with our verses. It does call us to be a particular kind of community, no matter what is or isn’t on the wall.

If you’re someone who has fought hard for these displays, I’m not questioning your love for God or your desire for moral clarity. I’m asking a different question: what kind of people are we becoming in the process?

What Beatitudes-shaped engagement might actually look like

It’s easy to stay abstract here, so let’s get concrete. What would it look like for the Beatitudes to shape how we move through a pluralistic public square?

Here are two simple scenarios.

1. The school board meeting

Your local district is debating policies around religion in schools. The room is packed. People are angry. Social media is already on fire.

Beatitudes-shaped Christians might:

Show up early and actually listen to those who disagree.

Speak calmly, without mocking or caricaturing others’ fears.

Acknowledge real concerns (about moral confusion, about kids feeling silenced) while being honest about the dangers of state-sponsored religion.

Refuse to cheer when “our side” lands a zinger, and look for creative compromises that protect both religious freedom and neighbor-love.

That’s peacemaking. That’s meekness. That’s hunger for righteousness that isn’t driven by humiliation or outrage.

2. The social media firestorm

A viral story breaks about a court blocking a new Ten Commandments law in your state. Your feed fills with Christian friends saying, “This is why America is collapsing.”

Beatitudes-shaped Christians might:

Resist the urge to share the angriest, most fearful posts—even if they “feel true.”

Post something measured that acknowledges the disappointment some believers feel while clarifying that students are still free to pray and that forced religious displays aren’t the same as faithfulness.

DM a friend who is clearly scared or furious and say, “I get why this hits you hard. Want to talk about it?”

That’s mercy and purity of heart in a space that rewards neither.

These may not seem glamorous compared to “winning a culture war,” but they look a lot more like the kind of kingdom Jesus actually described.

Losing power without losing our soul

As America becomes more pluralistic, Christians are going to have to decide what we really want.

Do we want guarantees of cultural influence—the comfort of knowing “our side” is still in charge, our symbols are still on the wall, our prayers are still coming over the loudspeaker?

Or do we want to become the kind of people Jesus described in the Beatitudes, whether we’re at the cultural center or pushed all the way to the edges?

When I was younger, I honestly believed that public Christian displays and school-led prayers were essential to faithfulness. I thought losing those things meant we were losing the country—and maybe losing God.

Now I’ve become more convinced of something else:

We can lose a lot of our public status and still be deeply faithful to Jesus. We can win every symbolic battle and still lose our soul.

Christians can keep putting most of our energy into protecting a certain image of “Christian America,” especially if that effort is driven by fear, nostalgia, and resentment. I know how tempting that is; I’ve felt those same fears.

Or we can receive this moment—less cultural dominance, more pluralism—as an invitation to re-learn what the New Testament has been saying all along: that we are exiles and sojourners, salt and light, a little flock entrusted with a very different kind of power.

The good news is that the Beatitudes weren’t written for people at the top of the heap. They were written for people who feel small, misunderstood, and sometimes pushed aside.

Which, come to think of it, might mean they were written for exactly this moment.

Maybe it’s time we stop fighting only to engrave the commandments on our walls—and let Jesus’ words in the Sermon on the Mount be engraved a little more deeply into us.