When Righteousness Turns Violent

How a summer with Operation Rescue taught me that empathy beats certainty

The pavement still held the night’s cool when we stepped onto the sidewalk in Chamblee. No signs, no chants—just three of us, heads bowed, the clinic’s glass doors flickering with fluorescent light. I told myself we were there for life. I didn’t ask what the women were there for. A young woman paused at the curb, clutching her purse with both hands, eyes fixed on the door. I didn’t see her face then; I only saw my cause.

I learned—too late—that moral certainty without empathy doesn’t sanctify us; it hardens us.

I grew up in suburban Atlanta in the 1970s and 80s, in a world where being a Christian and being a conservative were treated as nearly the same thing. My parents were solidly Republican — not activists, not firebrands, just typical middle-class Southerners who voted red and went to church on Sundays.

By the time I reached high school, I’d started to become more politically aware. I was drawn to the moral clarity of the issues that dominated the airwaves of that era — none more so than abortion. It felt, at least then, like the defining moral question of my generation.

That conviction — and the people it brought into my life — would lead me somewhere I couldn’t have imagined: into the heart of a movement that blurred the line between righteousness and rage.

Saturday Mornings Outside the Clinic

It started quietly enough. A friend of mine from school, Sharon, was a year older. She and one of her parents would go early on Saturday mornings to pray outside an abortion clinic in Chamblee, a working-class suburb northeast of Atlanta.

I asked if I could join. For nearly a year, I did — just the three of us, standing on the sidewalk, praying. We didn’t shout or hold signs or block anyone’s way. We thought of ourselves as peaceful witnesses.

I told myself we were standing for life, but I never thought about the lives already standing before me — the women themselves. Many were young, scared, and utterly alone. I saw them as an issue, not as people. Whatever compassion I believed I had was swallowed by conviction. They didn’t need me guarding a doorway; they needed someone to open one. If you were one of the women who walked past me on that sidewalk: I’m sorry. I made your hardest day harder. You deserved care, not my certainty.

Looking back, I know better. Even silent presence outside a clinic sends a message, and not one of compassion. We believed we were helping, but our very presence made a painful situation harder for the women walking through those doors.

Still, that experience opened a door — and not the one I thought it would.

The Summer Everything Changed

In the summer of 1988, the Democratic National Convention came to Atlanta. The city buzzed with journalists, delegates, and demonstrators. I began hearing rumors about a new pro-life organization planning a large protest — a group called Operation Rescue.

Their founder, Randall Terry, was young, intense, and fearless. I attended a local church where he spoke one evening — I believe it was Catholic, though I wasn’t. He spoke like a man on fire. He said abortion wasn’t just sin; it was murder. And he framed the fight against it not as politics but as spiritual warfare.

That was all I needed to hear.

Within weeks, Operation Rescue was organizing sit-ins across Atlanta. The movement had a strategy: block clinic doors, handcuff yourself to the building or to other protesters, refuse to leave. Police would come with bolt cutters, vans, and cameras. It was designed to create drama — and it worked. The protests made national headlines. The New York Times described “scores of arrests each day,” with protesters singing hymns as they were dragged away.

What felt, at the time, like revival was actually the early formation of what we now call the culture war.

The Motel 6 Headquarters

By midsummer, I was fully immersed. Operation Rescue had taken over a Motel 6 at Embry Hills as their informal headquarters. Prayer meetings in the lobby. Strategy sessions in the rooms. A constant flow of people — pastors, activists, college students, and families — all convinced we were on the frontlines of God’s battle for America.

Before long, they needed more space. And that’s when my parents — supportive but cautious — opened our home.

Our house became a kind of base camp. At any given time, two or three leaders stayed with us. Most nights were chaotic — people coming and going, phone calls, hurried meals. My parents drew one line: I wasn’t allowed to get arrested. They didn’t want a criminal record following me into adulthood. But they welcomed the activists. They even hosted dinners.

And among the people who came through our front door were Randall Terry, Joseph Scheidler, Kenneth Tucci, and one man whose name I’ll never forget.

Atomic Dog Slept in My Bedroom

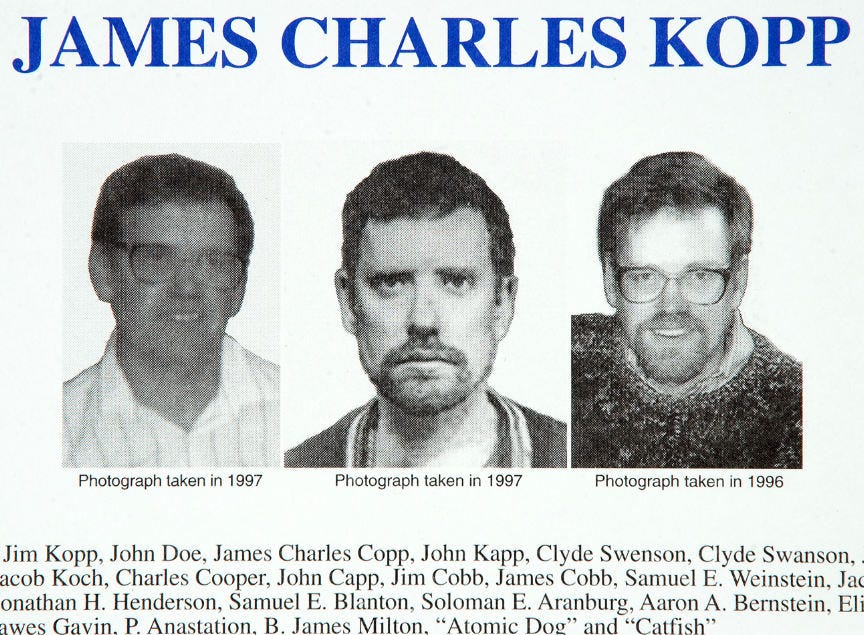

His name was Jim Kopp, though everyone in the movement knew him by his nickname — Atomic Dog. He was older than me, maybe late twenties. He had a shaggy beard, a disheveled charm, and the faint air of a man who thought faster than he spoke. He had studied biology at UC Santa Cruz, and he talked a lot about science — not just faith.

Sometimes, he’d talk late into the night about new tactics. He said he’d been thinking about chemical compounds that could damage the foundations of clinic buildings — or ways to make entrances unusable. I remember laughing it off. It sounded absurd, like movie-plot talk. He seemed eccentric, maybe a little unstable, but not dangerous.

Years later, when I was living in California, I saw his name in the news. He had murdered Dr. Barnett Slepian, a physician in Buffalo, shooting him through his kitchen window. He fled the country, made the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list, and was eventually captured and sentenced to life in prison.

The man who once slept in my bedroom became a domestic terrorist.

I want to be unambiguous: I repudiate Operation Rescue’s methods and the culture of moral emergency that excused them. I regret my participation — however “peaceful” I imagined it to be. I was part of a machine that added fear and shame to an already painful moment. That is on me.

Righteousness Feels Good — Until It Doesn’t

At the time, I was too young to understand the intoxicating power of moral certainty. Being part of Operation Rescue felt righteous. It felt like belonging. We weren’t just believing something — we were doing something. We were the ones willing to stand up for “truth” when the world stayed silent.

That’s what made it so dangerous.

I didn’t yet understand that righteousness without empathy turns cruel — that when your goal is purity, compassion starts to look like compromise. I saw myself as brave. In reality, I was becoming blind.

What I called “standing for life” was, in truth, a posture of judgment. I couldn’t imagine the fear or shame the women entering those clinics felt. I couldn’t picture their stories. I only saw ideology — and enemies.

I don’t just disagree with those tactics now; I believe they harmed people made in the image of God.

The Seeds of Today’s Extremism

Looking back, that summer in Atlanta feels eerily familiar. The language of the movement I joined has reappeared — louder, angrier, and now armed with political power.

Contemporary activist projects on the Christian right — often adjacent to groups like Turning Point USA, Moms for Liberty, and policy frameworks such as Project 2025 — lean on similar logic: We are defending truth. We are fighting evil. The ends justify the means.

But here’s what I’ve learned: When you claim moral monopoly, violence becomes not just acceptable — it becomes sanctified.

The culture war that began in the 1980s never ended. It just changed uniforms. Then, it was abortion clinics. Now, it’s school boards, elections, and statehouses. The slogans have evolved, but the spirit — that unexamined fusion of faith, fear, and political fury — is the same.

When righteousness turns violent, it isn’t righteousness — it’s idolatry of our certainty.

They Want the Ten Commandments, Never the Beatitudes

You can tell a lot about a theology by the scriptures it elevates. Today’s culture warriors love to talk about public displays of the Ten Commandments — laws, order, control. But you’ll rarely hear them campaign for public displays of the Beatitudes:

Blessed are the poor in spirit.

Blessed are the meek.

Blessed are the merciful.

Blessed are the peacemakers.

The difference says everything. The Commandments are about behavior; the Beatitudes are about character. And it’s much easier to control behavior than to cultivate character.

That’s what I missed as a teenager — and what much of the American church still misses today. We keep fighting for moral authority, when the Gospel calls us to moral humility.

The Long Unraveling

When I left for Auburn University in 1990, I tried to keep my activism alive. I joined the local pro-life group and the College Republicans. But gradually, I began to notice the same patterns of hypocrisy and manipulation I’d seen before — people bending truth in the name of “principle,” using fear to mobilize the faithful.

By my sophomore year, I was done. I wanted nothing to do with politics.

Still, the shame lingers even now — not just for what I did, but for what I failed to see. I once believed I was defending life, but in truth, I was defending my own sense of righteousness. I look back with deep embarrassment that I ever mistook confrontation for faithfulness.

What We Chose — and What We Lost

I know there are people who will read this and say, “But you were right. You were defending the unborn.” But that’s the hardest part — realizing that “rightness” without love is still wrong. I’ve come to see that repentance isn’t only for what we do to others, but for how easily we convince ourselves we were the good ones.

A truly pro-life ethic, I’ve come to believe, must extend beyond the unborn. It must care just as deeply for the women facing impossible choices, for the children already here, and for the poor and oppressed struggling to survive. The Gospel doesn’t let us divide life into categories of the innocent and the undeserving. Life is sacred — all of it — or it’s just another slogan we use to feel righteous.

That’s why I now see empathy not as weakness, but as discipleship. To feel the pain of others — even those we disagree with — is to see them as God does.

When righteousness turns violent, it’s no longer righteousness. It’s idolatry — a worship of our own moral certainty.

If you’ve ever felt that hard edge in yourself — as I did — try pausing for the person in front of you before the principle you carry. The good news is that empathy is something we can practice, not a pass we must earn.

To women who have faced this decision: I won’t pretend to know your story. I can only say I wish I had chosen to listen before I chose to judge.

How many more people must we wound in the name of saving souls?

Further Reading

History of Operation Rescue (Wikipedia) — movement overview

“Atlanta Protests Prove Magnet for Abortion Foes” — The New York Times (contemporaneous reporting)

“Killing Kittens, Bombing Clinics” — Facing South (historical context)

“Abortion Clinic Under Siege” — Deseret News (on-the-ground coverage)

“A Violent History” — SPLC (extremism background)

Another thoughtful and insightful piece of writing.

Being able to distill individual acts into larger frameworks is something sorely lacking today but which you seem to do naturally.

I agree that empathy is probably the characteristic that separates us. It's too bad that some leaders are trying to make it a sign of weakness or a sin.

Rock on, my friend. Keep examining.