The Good Old Days for Whom?

On nostalgia, fear, and the memories we refuse to inherit.

I’ve seen the photo a dozen times.

Black-and-white. Young white students. Hair done. Books in their arms. Faces twisted in a kind of collective fury—mouths wide open, shouting like something sacred is being stolen from them.

They’re white high school students in Montgomery, Alabama, protesting the integration of their public schools.

For a long time, it registered as “history.” A sealed chapter.

And then I did the math.

The photo is from 1963.

That’s less than ten years before I was born.

Which means those weren’t ancient villains. Those were somebody’s youth group kids. Somebody’s Sunday school class. Somebody’s choir section. People close enough to my parents’ age that I likely shook hands with their peers in church foyers and fellowship halls during my lifetime.

That’s what I can’t unsee anymore: the past isn’t past. It’s often just… nearby.

“Take the country back”

Over the years, I’ve heard Christians talk about “taking the country back for Christ” and returning to the “good ol’ days.” Sometimes it’s said with a sigh. Sometimes with a clenched jaw. Sometimes with the kind of certainty that makes you feel like you’re supposed to say amen.

Every so often, I ask a simple question:

“What time are you talking about?”

More than once, the answer has been immediate: the 1950s.

So I ask the question that changes the temperature in the room:

“How were those good ol’ days for Black people? For women? For people who weren’t welcome in half the rooms where decisions were made?”

And what I’ve gotten most often isn’t an argument. It’s not even a defense.

It’s a kind of silence. A pivot. A vague “well, you know what I mean.” Sometimes a subtle annoyance that I’d even ask.

That silence tells me something important: for a lot of us, nostalgia is not a memory. It’s a mood. And moods don’t like being fact-checked.

The question isn’t whether the past had strengths. It’s whether we’re willing to tell the whole truth about what those “good ol’ days” required from the people who weren’t protected by them.

Nostalgia is a mood—but for a lot of our neighbors, the past is a memory with consequences.

Desegregation Wasn’t Ancient History

I grew up in DeKalb County, Georgia—Atlanta metro. And my school district wasn’t desegregated because the whole community collectively woke up one day and decided to do the right thing.

It was under a federal court order.

Up until seventh grade, my school world was overwhelmingly white—95% white, easily. Not because I was trying to curate a bubble, but because that’s how the bubble was built. It felt normal because it was all I knew.

Then I started high school in eighth grade.

I remember sitting at lunch—plastic trays sliding, the low roar of a cafeteria I didn’t yet know—looking around and realizing I was the only white kid at my table.

It wasn’t persecution. It wasn’t injustice. But it was disorienting in the way reality often is when you’ve been sheltered from it. It forced a question I hadn’t really asked yet: If my “normal” could be that segregated without me even trying, what else was I not seeing?

I was socially outnumbered for a moment; I wasn’t structurally endangered in the slightest.

What felt like an “awakening” for me was simply everyday reality for others.

A big reason for that shift was the Majority-to-Minority (M-to-M) program—one of the mechanisms used to further desegregation efforts.

That’s not me trying to make myself the hero of the story. If anything, it’s me admitting how passive I was. I didn’t “seek diversity.” I was simply placed in a more honest version of the world.

And honesty is a gift, even when it’s uncomfortable.

The “good ol’ days” were close enough to touch

Not far from where I grew up was Forsyth County, Georgia.

I remember hearing about it as a teenager—late high school years. It didn’t fully register at the time. Maybe because I didn’t have the categories. Maybe because I didn’t want it to register. Maybe because white teenagers can go a long time without needing to look directly at certain things.

But a few years later, it hit me how outrageous it was: there was a county not far from Atlanta where Black people were—at minimum—clearly not welcome. In a Supreme Court case describing the county’s history, Forsyth in 1987 is described as still 99% white, and civil-rights marchers are described as being met by crowds shouting slurs and throwing rocks and bottles.

Again: this isn’t ancient.

This is within living memory. This is “people you might sit next to in church” proximity.

Which means when someone says “back to the good ol’ days,” I can’t help but wonder whether they’re thinking about economic stability and cultural cohesion… or whether they’re gravitating toward a social order that functioned by keeping some people in their place.

A lot of people would be offended by that suggestion. I get it. Most folks don’t think of themselves that way.

But intent doesn’t erase impact. And nostalgia doesn’t become righteous just because it feels comforting.

And it’s worth saying out loud: Atlanta has always carried two stories at once. We’ve loved the self-image—the city “too busy to hate.” But slogans can be marketing as much as memory. A place can celebrate moderation while still living with deep segregation and quiet exclusion.

The Stories That Formed Me

Here’s another uncomfortable piece of my own formation.

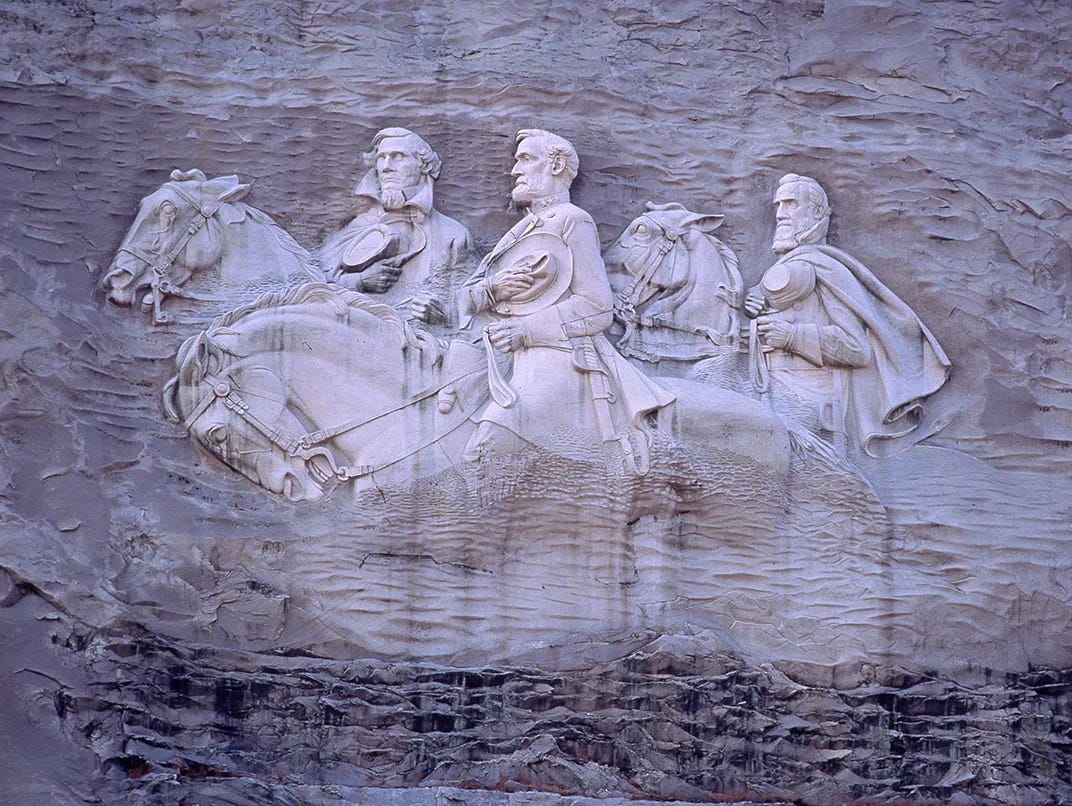

I grew up going to the laser show at Stone Mountain as a kid. It was just… a thing you did. Family outing. Summer tradition. You didn’t think about it too hard.

At some point in high school—likely because I was around Black people more—I began to realize that much of that show was a Confederate tribute. The laser show didn’t just happen near Confederate symbolism—it famously projected onto the carving itself.

In other words: something that felt like harmless local culture wasn’t harmless at all. It was telling a story. It was honoring a memory. It was forming people.

And it had been forming me, long before I had the words for what was happening.

This is one reason I struggle with the “it’s just history” defense. History is never “just” history. It always comes packaged with interpretation: who’s honored, who’s minimized, who’s made invisible, who’s expected to swallow it quietly for the sake of tradition.

Howard Thurman—an Atlanta-shaped voice if there ever was one—wrote about what faith sounds like to people who live under threat and scarcity, people he called “the disinherited.” He understood something many comfortable Christians forget: you can’t preach about courage the same way when your body has always been the one at risk.

Nostalgia is a mood—but for a lot of our neighbors, the past is a memory with consequences.

When ‘Tradition’ Wore a Uniform

When I went to Auburn University in 1990, I ran into another version of the same dynamic.

The KA fraternity had an annual parade through town in Confederate uniforms—presented as tradition, pageantry, school spirit, old South nostalgia dressed up as harmless fun. I arrived at Auburn in 1990. By the early ’90s, the KA “Old South” parade—Confederate uniforms and all—was shut down.

My first reaction was confusion.

Then it turned into anger.

I think I was naïve about racism at that time. Not that Atlanta was perfect—far from it—but I’d had limited experience with racism that blatant, that public, that proud. I wasn’t prepared for it. I also wasn’t prepared for how quickly some people could call it “no big deal,” as if the only people qualified to name harm were the ones who weren’t harmed.

And here’s the part I’m not proud of: I didn’t participate in the protest.

I can make excuses. I can talk about immaturity or uncertainty or not wanting to be noticed. But the simplest truth is this: I had the option to stay on the sidelines, and I took it.

That’s not virtue. That’s comfort.

And if I’m honest, that’s part of what I’m trying to interrogate in this essay: the way comfort disguises itself as righteousness.

C.T. Vivian spent his life challenging the respectable version of injustice—the kind that survives because decent people keep their hands clean. And I can’t think about that without seeing myself: how often my “prudence” was just avoidance, how often my desire for peace was really a desire not to be bothered.

“The talk”

Over time, I’ve been fortunate to have Black friends who were patient and kind enough to teach me about the systemic racism they’ve faced. I don’t say that as a badge. I say it because their patience exposed how much I’d been able to live without seeing.

One of the things that lodged in my chest early on was learning about “the talk.”

Not the birds-and-the-bees talk.

The other one.

By “the talk,” I mean the conversation many Black parents have with their kids about navigating racism—and especially how to handle encounters with police and other authority figures in ways meant to reduce risk and make it home safely.

And what stuck with me wasn’t just the advice—it was the grief of having to give it.

Once you’ve sat with that, it becomes harder to hear certain Christian fears the same way.

Because what many white Christians call “persecution” is often the loss of preference.

And what many minorities call “fear” is a learned response to history—personal, communal, and sometimes generational.

And it’s worth saying: Black Atlanta has never only been defined by what it endured. It has also been defined by what it built—churches, neighborhoods, institutions, art, community—often in the face of what was designed to break it.

Choosing Proximity Over Theory

Around that same season of my life, I joined the gospel choir in college.

I don’t have a cinematic story attached to it. No single friendship that “changed everything.” No neat redemption arc.

The honest reason is simpler: Auburn felt far whiter than my high school, and I wanted something closer to normal—meaning, I wanted to be around Black people in a way that wasn’t theoretical.

That’s not me saying “I have Black friends, therefore I’m enlightened.” I’m allergic to that kind of self-congratulation, and I know how easily it becomes a substitute for actual humility.

If anything, joining that choir was an admission that I needed proximity. I needed relationship. I needed to be around people who saw the world differently than I did—not as a debate exercise, but as a way of becoming less stupid.

And over time, that kind of proximity changes you.

Not because it makes you morally superior.

But because it makes your world more real.

What this has to do with Christian nationalism and fear

Here’s the connection I’m trying to make as gently—and as clearly—as I can.

When white Christians talk about “taking the country back for Christ,” they often imagine they’re fighting for moral clarity and spiritual renewal.

But for many Black Christians, immigrant believers, and global Christians—especially those who have lived under authoritarian regimes—the phrase “Christian nation” doesn’t sound like revival.

It sounds like state power.

It sounds like the powerful using God-language to secure social control.

It sounds like “you’re welcome here, as long as you don’t challenge the order.”

Howard Thurman put it plainly: “Too often the weight of the Christian movement has been on the side of the strong and the powerful…”

And that line won’t leave me alone, because it describes a temptation we can spiritualize: when faith starts to feel like a tool for protecting comfort, it’s already drifting toward coercion.

And this is where the “good ol’ days” conversation becomes more than a throwaway line. Because “back” is never neutral. Back means a specific arrangement of power. Back means someone gets protected and someone gets policed. Back means someone gets the benefit of nostalgia and someone else gets asked to swallow it.

If you grew up never needing “the talk,” you can romanticize eras that other people remember as dangerous.

That doesn’t make you evil.

But it does mean your memory might be incomplete.

And it’s not just history. Even here in Atlanta, the question of who gets to feel “at home” is still alive. Metro Atlanta ranks among the most affected regions when it comes to gentrification eliminating majority-Black census tracts and displacing longtime residents—so “back” isn’t just a slogan, it’s a force that can push people out of the places that hold their memories.

To Be Fair

I want to be fair here.

A lot of Christian fear today is not manufactured out of thin air. People see cultural fragmentation. They see families struggling. They see loneliness and addiction and distrust. They see institutions wobbling. They see kids being discipled by screens. They feel like the country is changing faster than they can process.

I understand that. I share some of it.

But the danger is when fear makes us reach for power as a shortcut to faithfulness.

When fear makes us confuse “Christian influence” with “Christian control.”

When fear makes us imagine that if we can just reinstall the right symbols, the right laws, the right leaders, the right public prayers… we’ll finally be safe again.

If your strategy for discipleship is dominance, something has gone wrong.

And if your version of “Christian America” requires other people to feel unsafe—or invisible—for you to feel at home, that’s not renewal. That’s regression.

The question that keeps haunting me

When I think about that photo—students shouting, faces full of conviction—I don’t just think, “How could they?”

I think: How easy would it be to stand in that crowd without realizing what I was becoming?

Because that’s the thing about crowds. They don’t feel evil from the inside. They feel justified.

Which is why “take the country back for Christ” language makes me nervous. Not because I think everyone who says it is a monster. But because I’ve seen—up close—how quickly “righteousness” can become a costume for fear.

And I’ve seen how recently all of this was normal.

So I’m asking—first of myself, and then of anyone willing to hear it:

When you say “back,” back to what?

And when you say “for Christ,” for whom?

A Better Way Than “Back”

If you’ve read this far and you feel defensive, I understand. I’ve been there. It’s hard to be told your nostalgia has blind spots. It’s hard to realize that what felt like “home” to you felt like “threat” to someone else.

But I also believe this is part of Christian maturity: letting other people’s memories correct our mood.

Not as an act of shame, but as an act of truth.

Not to score points, but to love our neighbors more honestly.

Maybe the invitation here is simple:

Before we talk about taking anything “back,” we should sit with the people who remember what “back” cost them.

And maybe the most faithful move isn’t to grasp for control.

Maybe it’s to choose proximity. To listen. To lament what was unjust. To repent where we’ve been passive. To tell the truth about our history without flinching.

Try one of these:

Ask one clarifying question in real life

“When you say ‘the good ol’ days,’ what year are you picturing—and who did that version of America work for?”Practice “memory substitution”

Before repeating a nostalgic political line, intentionally pair it with one story you’ve heard from a Black friend, immigrant pastor, or elder who lived the downside of that era.Local history honesty

Learn one uncomfortable fact about your county (housing covenants, school zoning, sundown practices, etc.) and talk about it with your family—not online.Church audit (quiet, not dramatic)

Notice how often your church’s political anxieties are framed as “persecution,” and ask: “Is this about faithfulness—or about losing preference?”Proximity with purpose

Not “collect diverse friends,” but “show up consistently” in a shared space (community group, choir, service org) where you’re not the cultural default—and listen more than you speak.

Because Christianity doesn’t need nostalgia to be true.

It needs courage. And humility. And love.

And here’s the hopeful part I’m trying to hang onto: the church can still tell the truth and become more beautiful for it. Not by winning the culture war, but by becoming the kind of people who don’t need a myth to be faithful—people who can repent without collapsing, listen without defensiveness, and love our neighbors without needing them to be quiet first.

Question to sit with: If I’d been there, what crowd would I have joined—and what would it take to make sure I don’t join it now?