From Satanic Panic to QAnon: How Fear Became a Christian Virtue (and Why It Isn’t)

Fear might win elections. It does not make disciples of Jesus.

I grew up in a Christianity where the end of the world was always just around the corner—but not in the poetic, “Jesus will come again someday” sense.

I mean the Rapture.

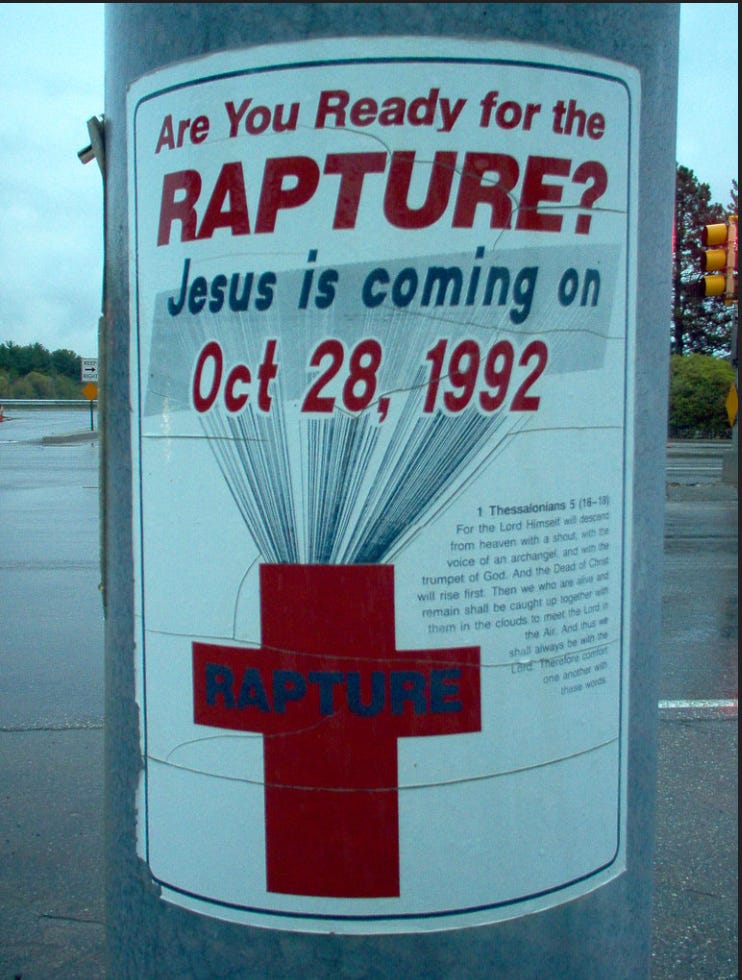

If you were an American evangelical teenager in the 80s and 90s, you probably breathed that air too. One day, without warning, all the real Christians would vanish. Planes would fall from the sky. Cars would crash on the interstate. Clothes would crumple in empty church pews. And if you were still here, well… that told you something terrifying about your salvation.

The Rapture wasn’t just a doctrine; it was a mood.

It floated around in sermons and youth talks, but it also came wrapped in fiction. Frank Peretti’s spiritual-warfare thrillers—This Present Darkness and Piercing the Darkness—sold millions of copies and helped define a whole genre: small-town America as the front line of an invisible war, with demons lurking behind school board meetings and angels waiting for enough prayer “fuel” to intervene.

Peretti never wrote a systematic theology of the end times, but his novels lived in the same imagination as prophecy conferences, end-times movies, and later the Left Behind series. Together they trained a generation to see history as a countdown clock and “the culture” as one big spiritual battleground.

Looking back now, I’m struck by how new and narrow that story actually is. The popular “secret rapture” timeline—believers snatched away before a seven-year tribulation, Antichrist, one-world government—doesn’t come from the early creeds. It emerges in the 19th century with John Nelson Darby’s dispensational premillennialism, spreads through the Scofield Reference Bible, and becomes dominant in certain American evangelical circles. For most of church history, Christians didn’t divide time into neat dispensations or imagine believers vanishing while everyone else was “left behind.”

Most of us never heard that part. We just heard that at any moment Jesus might quietly take the real Christians and leave the rest of us staring at empty clothes.

If you’ve ever sat in a youth room after a sermon like that, you’ve seen the fruit: “recommitment” after recommitment, altar calls filled with kids praying just in case the last one didn’t stick. Today, people have language for that—“rapture anxiety,” the chronic dread that you might wake up one morning to an empty house and realize you were never truly saved.

I watched that cycle up close.

Interestingly, I wasn’t the most anxious kid in the room. I didn’t spend nights staring at the ceiling, convinced the Rapture would happen before my next birthday. But I saw how many of my peers lived in a constant low-grade panic about being “left behind.” Even if you weren’t the anxious one, you were still swimming in a story where fear did a lot of the discipleship.

If you can convince a 15-year-old that one misstep might reveal they were never truly saved, you don’t have to spend much time casting a positive vision of life with God. Fear will keep them in line.

And I’m writing this now because in just the last five years, I’ve watched people I’ve known my whole life—once steady, grounded folks—become consumed by fear and anger. Not because their day-to-day circumstances dramatically changed, but because their media diet did. It’s straining relationships everywhere I look.

As I’ve reflected on my upbringing, I’ve realized the Rapture was just one expression of a much larger pattern.

Fear wasn’t just in the air. Fear was one of the main discipleship strategies.

The Things We Were Taught to Fear

If I had to make a short list of the things we were taught to fear in my evangelical world, it would go something like this:

Rock and roll

Homosexuality

Communism

Liberalism

Satanism

Those weren’t abstract theological concerns. They were presented as live threats—to our souls, our families, and America itself.

Two of them, in particular, came with very specific stories attached.

Rock and roll: the devil in the turntable

At some point, my parents got hold of a book called Hell’s Bells: The Dangers of Rock ’n’ Roll—a Christian “exposé” on rock music and its supposed connection to sex, drugs, rebellion, and the occult. It ran as both a book and an influential documentary series in 80s evangelical circles.

The message was simple: the music your kids are listening to is not just questionable; it is spiritually dangerous.

My brother and I were deeply into music. We actually knew the bands and albums being name-checked. My parents didn’t; they were encountering this world mostly through Christian warnings about it.

So there was a moment when they came to us worried about our music. They had been reading or watching Hell’s Bells material and did what good, concerned Christian parents were told to do: intervene.

We did what good, slightly annoyed teenage sons were going to do: we started checking the claims.

One of the famous ones was about Led Zeppelin. We were told that if you played certain records backward, you could hear hidden satanic messages—backmasking that would supposedly worm its way into your subconscious. Hell’s Bells leaned hard on these examples, treating them as smoking-gun proof of a demonic agenda.

But we had the albums. We listened. We knew the songs.

And we knew, very quickly, that a lot of what was being said just wasn’t true. Or at least, if you had to strain your ears and your imagination that hard to hear the “message,” then maybe the real power of rock music wasn’t in secret backwards phrases—it was in the emotions, identity, and community it offered restless teenagers.

For me, that experience didn’t create fear. If anything, it created skepticism—not about God, but about the people who were so sure they were speaking for him.

A lot of kids didn’t have our level of familiarity with the music, though. Their parents didn’t either. The net effect was that an entire sonic world—from The Beatles to Zeppelin to Madonna—got cast as a spiritual threat.

Once again, fear did more work than discernment.

Satanism: from Warnke to Rebecca Brown to QAnon

If rock and roll was one front in the spiritual war, Satanism was the dark, shadowy other.

In the 80s and early 90s, a wave of books and testimonies hit evangelical circles claiming to reveal secret satanic cults. Mike Warnke’s memoir The Satan Seller told the story of his supposed life as a high-ranking Satanist before converting to Christianity. The book became a religious best-seller and launched Warnke as a go-to “expert” on Satanism—until a detailed investigation exposed major parts of his story as fabricated.

Then there were even more graphic accounts like Rebecca Brown’s He Came to Set the Captives Free, which described elaborate satanic rituals, child sacrifices, and a vast hidden network of occult activity.

If you took these books at face value—and many Christians did—you could easily walk away believing that in certain neighborhoods, behind certain doors, there were Satanists sacrificing children in secret ceremonies. Layer that onto the broader “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s—false allegations of ritual abuse at daycares, sensational talk shows, breathless news specials—and you get a potent cocktail of moral concern and conspiracy thinking.

It’s not hard to see why this landed. If you already care deeply about children and you already distrust a lot of the institutions meant to protect them, of course you’ll be vulnerable to stories that promise to finally “tell the truth” about hidden evil.

Again, I wasn’t walking around convinced that every cul-de-sac hid a satanic coven. But I know people who did feel that dread. And in retrospect, I can see how those narratives primed a lot of Christians for later conspiracies.

Fast-forward a few decades and you get QAnon: a sprawling, internet-born conspiracy framework claiming that a secret global cabal of satanic pedophiles—liberal elites, celebrities, politicians—preys on children, and that a particular political leader is uniquely chosen to stop them.

Some horrors are not conspiracy theories. Jeffrey Epstein and the abuse he facilitated are tragically real. Christians should care deeply about protecting children and exposing actual exploitation.

But there’s a straight emotional line from:

“There are Satanists sacrificing children in your town; only we see it”

to

“There is a secret satanic pedophile cabal running the world; only we see it.”

The details evolve; the pattern stays the same. You cultivate a community perpetually on the lookout for hidden, almost unimaginable evil. You feed them stories that are hard to verify but easy to feel. And then you link their vigilance to their faithfulness:

“If you’re truly awake spiritually, you’ll see this. If you don’t see it, maybe you’re compromised.”

Once again, fear becomes the test of faith.

From Satanists to Obama to Trump

If the 80s and 90s were about Satanists in your daycare and demons in your cassette tapes, the 2000s and 2010s simply updated the cast of villains.

Take Barack Obama.

You didn’t just get normal partisan disagreement over policy. You got the birther movement: the insistence that he wasn’t really a natural-born citizen and was therefore illegitimate as president. Wrapped around that was a quieter but persistent story—that he was secretly Muslim, maybe even a “closeted jihadi,” and that electing him would usher in Sharia law in America.

None of this was true. Obama is a Christian. Not every evangelical believed those rumors—many rejected them outright—but white evangelicals were one of the groups most likely to believe he was Muslim, with some surveys finding roughly a third saying so.

That’s not just trivia. It’s a discipleship story.

If you’ve been formed for decades to see the world as a battleground between righteous insiders and dangerous outsiders, and been told that secularism, liberalism, and Islam are existential threats, then “Maybe the president is secretly with them” doesn’t sound wild. It can sound spiritually perceptive.

The content shifted—from Satanic cults to “stealth jihad”—but the emotional logic stayed put:

There is a hidden enemy.

The elites won’t tell you the truth.

If you don’t see it, you’re naïve—or faithless.

That same logic slid almost seamlessly into the Trump era.

Whatever else you think about Donald Trump, he knows how to weaponize fear. From launching his 2016 campaign by describing Mexican immigrants as criminals and “rapists,” to painting a picture of “American carnage” at his first inaugural, to the constant talk of “invasion” and “they’re taking over,” his political imagination runs on threat.

Again, not every evangelical fell in line. Some opposed him from the beginning. But many of the Christians who did support him were listening through years of prior formation that had taught them to expect existential threats around every corner.

Fear of:

Liberal judges

“Marxists” in universities and classrooms

Immigrants “invading” the border

LGBTQ neighbors “grooming” children

An “authoritarian left” that will erase Christians from public life

Those aren’t fringe anxieties. They are mainline talking points in parts of the MAGA media ecosystem, repeated daily by pundits and “Christian” influencers.

We’ve seen this in specific stories:

Immigration described as an “invasion,” even when data suggests immigrants—including undocumented ones—are not committing crime at the rates implied, and in many cases less than native-born citizens.

LGBTQ neighbors treated not as people to understand and love, but as a civilizational threat “coming for your kids”—whether through Drag Queen Story Hour, school policies, or basic civil protections.

There is plenty of room for thoughtful debate here. Parents asking hard questions about what is age-appropriate for their kids, or how much say they should have in school curricula, are not automatically bigots. Those are real concerns that deserve honest conversation.

But a lot of the rhetoric skips that nuance entirely. It goes straight for the existential register: “They are after your kids.” If you’ve already been discipled to believe that hidden networks of evil are trying to corrupt children, this lands on a well-prepared heart.

Great Replacement talk, the idea that “they” (immigrants, racial minorities, global elites) are going to “replace” “real” Americans, creeping from fringe spaces into more normalized rhetoric about demographic “invasion” and loss of “our” country.

And more recently, in the world you and I inhabit online, we see the same playbook when Christians like Gabe Lyons compare a democratic socialist city councilman like Zohran Momdani to Joseph Stalin. That’s not there to help you understand New York politics. It’s there to hit all the old fear buttons: Marxism, gulags, Soviet terror, “they’re going to destroy everything you love.”

You don’t need to know Mamdani’s actual record or platform if you’ve already been discipled to hear “socialist” and see Stalin’s mustache.

From Hell’s Bells to Satanic Panic to birtherism to QAnon to “American carnage,” the cast of characters changes. The discipling emotion often doesn’t.

Far too often, it’s fear.

COVID, Media, and the Discipleship of Panic

If any season exposed how deep this runs, it was COVID.

To be clear: everyone, in every community, wrestled with fear, confusion, and bad information during the pandemic. Institutions made mistakes. Guidance changed. People lost loved ones and jobs, and the ground felt like it was constantly shifting. None of that is trivial.

But something specific happened in chunks of American evangelicalism.

Studies found white evangelicals among the most resistant to masks and vaccines. For some, that resistance was framed as principled skepticism, a concern about government overreach, or simple exhaustion after years of conflicting messages. Those are understandable instincts, especially if you already have a deep mistrust of political and media institutions.

In a lot of spaces, though, the conversation moved into something else: apocalyptic talk about religious persecution, rumors that vaccines were the “mark of the beast,” and social media posts insisting that any public health restrictions were part of a plot to crush the church.

I’m not going to relitigate COVID policy here. I simply want to name what I’ve seen, especially in the last five years: people I’ve known my entire life—people who were by all appearances relatively grounded—becoming consumed by fear and anger.

The common denominator hasn’t been their local church. It’s been their media diet.

Hours a day on YouTube. Algorithm-curated doom scrolls on Facebook and X. A steady drip of “did you hear?” forwarded in group texts. When your discipleship program is built around the most alarming clips the internet can surface, it will do exactly what it is designed to do: make you angry, make you afraid, and make you suspicious of anyone who doesn’t share that emotional state.

I say that as someone who has felt that pull too, not as a detached critic looking down at everyone who watches cable news or scrolls Instagram.

I’ve watched this fracture relationships.

Not because we disagree on tax rates or school board policies, but because one side is living in a constant state of emergency and the other is simply… not. It’s hard to break bread together when one person is convinced the house is on fire and the other is trying to talk about hope.

And here is where I want to say something very clearly:

As Christians, we are not called to be naïve.

But we are absolutely not called to be discipled by fear.

Which brings me to Scripture.

“Do Not Be Afraid” Is Not a Side Note

There’s a popular Christian meme that says the Bible commands “fear not” 365 times—one for every day of the year. That’s not actually true; when you count variations like “fear not,” “do not fear,” and “do not be afraid,” you get just over a hundred instances, depending on translation.

But honestly? Once would be enough.

The point isn’t the exact number; the point is the pattern.

From God speaking to Abraham and Israel’s prophets, to angels announcing Jesus’ birth and resurrection, to Jesus telling anxious disciples not to be afraid, Scripture is soaked in variations of the same command and comfort:

Do not be afraid.

Do not fear, for I am with you.

Take courage; it is I.

Peace be with you.

In almost every one of those moments, “do not be afraid” isn’t a barked order to toughen up. It’s anchored in presence:

Do not be afraid, for I am with you.

It is I; do not be afraid.

My peace I give you.

It’s astonishing how little oxygen this gets in some Christian circles compared to the oxygen devoted to listing all the things we should supposedly fear.

We can recite “do not be afraid” as memory verses while streaming hours of content designed to keep us in a permanent emotional emergency. We can quote “perfect love drives out fear” on Sunday and marinate in “they’re coming for you” Monday through Saturday.

Something about that should trouble us.

A Different Gospel Story: Not Escape, but New Creation

Part of the problem, I think, is the underlying story many of us were handed about what the gospel is.

In a lot of American churches, the gospel was essentially framed as an escape plan: this world is going to burn, history is on a downward spiral, and the goal of faith is to make sure your soul goes to heaven when you die (or when the Rapture comes) instead of somewhere worse.

If that’s the story, constant fear makes a kind of sense. Why bother with hope for this world if its main function is to be a sinking ship?

N. T. Wright and others have spent years pushing back against that framing. Wright loves to say that the point of Christianity is not “to go to heaven when you die,” but that in Jesus, the living God has become king of the world.

In his vision of the New Testament, the gospels aren’t just the pre-story before Paul’s “real” theology. They are the announcement that God’s kingdom—God’s saving, healing reign—is breaking into this world through Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, and will one day be fully revealed in a renewed creation.

That story doesn’t minimize evil, injustice, or suffering. It does something more radical: it insists that God’s final word over his world is not abandonment but renewal.

J. R. R. Tolkien coined a word for this in his essay “On Fairy-Stories”: eucatastrophe—literally, a “good catastrophe,” a sudden, joyous turn in the story that comes when all seems lost.

For Tolkien, the resurrection of Jesus is the great eucatastrophe of history: the moment when the worst thing and the best thing collide, and joy bursts out of apparent defeat.

There’s a scene in The Return of the King where Sam wakes up after the ring is destroyed and sees Gandalf alive again. In amazement he asks, “Is everything sad going to come untrue?”

That question has lodged in the Christian imagination for good reason. It sounds a lot like the New Testament’s vision of resurrection and new creation: not just that some new good things will happen somewhere else, but that somehow, in ways we can’t yet fully grasp, the deep sadness of this world will be undone and healed.

If that is the gospel story—the God who says “do not be afraid,” the King whose presence is with us now, the One committed to making all things new—then a Christian posture of permanent, all-consuming fear starts to look less like faithfulness and more like forgetfulness.

So What Do We Do With Our Fear?

I wish I could say I simply flipped a switch one day and stopped being afraid of everything.

That’s not how this works.

I still feel fear. I still get anxious about politics, culture, my kids’ future, the state of the church. I still feel the tug of outrage when a headline hits just right. I still have to watch my own media habits.

But I’m trying, haltingly, to be discipled by Jesus more than by cable news and YouTube.

Here are a few practices that help me, offered not as spiritual heroics but as small acts of resistance:

1. Pay attention to the fruit.

After I consume a piece of media—a podcast, a clip, an article—I ask: What did that produce in me? If the answer is more fear, cynicism, and contempt, I take that seriously. The Holy Spirit produces love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. If my media diet consistently produces the opposite, I need to be honest about who is discipling me.

2. Limit the firehose.

I don’t owe every pundit or “Christian commentator” unlimited access to my nervous system. Curating what I consume is not denial; it’s a way of protecting my ability to be present to God and other people.

3. Seek real conversations with “the other side.”

Sitting across the table from people I was told to fear—immigrants, LGBTQ neighbors, people with very different politics—has done more to heal fear in me than a hundred hot takes. It doesn’t mean I agree with everyone. It just means I let actual humans interrupt the caricatures.

4. Return to the Gospels regularly.

When I give more attention to Jesus’ words and ways than to the latest panic, it becomes easier to notice when the “Christian” messages in my feed are running on fear rather than faith.

5. Name and grieve the relational cost.

Part of resisting fear is lamenting what it has already broken. I’ve seen relationships strained or lost because one person’s media diet pushed them into a constant state of alarm. Naming that loss—not in smugness, but in grief—reminds me what’s at stake.

And because I don’t want this to sound like it’s all bad news, I should say: I do see pockets of non-anxious discipleship. I know churches that are quietly refusing to build their identity around outrage. I’ve watched friendships survive deep political disagreement because both sides chose curiosity over caricature. I see Christians doing ordinary works of mercy while the algorithm begs them to rage-share one more clip. Those small things matter.

Called to Hope, Not Panic

None of this is an argument for sticking our heads in the sand. There are real injustices in our world. There are policies Christians should care about. There are moments when courage looks like saying “no” to genuine evil.

But courage is not the same as panic.

The New Testament does not call us to be the most frightened people in the room. It doesn’t command us to believe every dark rumor, to share every alarming meme, or to live in permanent outrage at our neighbors.

It calls us to trust the One who walks into locked rooms full of anxious disciples, breathes peace on them, and says, in various ways, “Do not be afraid.”

Fear might win elections. It might drive ratings. It might keep people glued to their phones.

But it cannot make us look like Jesus.

Somewhere along the way, we have to decide whose voice will have the loudest say in our emotional life: the voices profiting from our anxiety, or the King who promises that, in the end, in ways we can barely imagine from here, everything sad is going to come untrue.

I don’t have this all figured out. I still catch fear discipling me in all kinds of subtle ways.

But I want my life—and the lives of the Christians I love—to be animated less by “What if they come for us?” and more by “What might God be making new right here, right now?”

We are called to be a people of hope, not of hysteria.

And maybe the first step toward that is as simple, and as difficult, as finally taking seriously the command we’ve been given again and again:

Do not be afraid.

So here’s my question for you: In the quiet, honest places of your life, who is actually discipling your emotions—Jesus, or the loudest voice that profits from keeping you afraid?